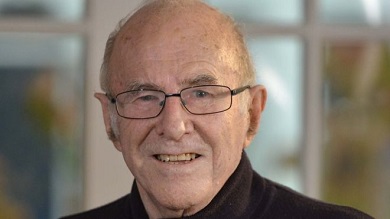

Clive James RIP

Yesterday my brother gave me a lift from the south coast back to my home. On the way I commented that we should remember the date Wednesday 27th November 2019 because one day in some far off Pub Trivia Quiz it was possible that the question might come up as to which three culturally-significant Brits had their deaths announced upon it.

With due respect to celebrity chef Gary Rhodes and polymath Jonathan Miller, for me the passing of writer and broadcaster Clive James – though long anticipated because of his terminal illness – was that which affected me most.

With due respect to celebrity chef Gary Rhodes and polymath Jonathan Miller, for me the passing of writer and broadcaster Clive James – though long anticipated because of his terminal illness – was that which affected me most.

I was a huge fan.

For present purposes I shall leave the learned reviews of the sheer breadth of his work to the obituary writers.

He was a rare animal, a constantly enthusiastic and inquiring man who read widely and voraciously tens of subjects – academic, every genre of literature, history, science and popular culture among them – and yet retained an uncanny ability to discuss, explain and comment upon them (or indeed anything else he turned to) in a manner that allowed lesser mortals like me to appreciate and understand them better, frequently for the very first time.

He was a rare animal, a constantly enthusiastic and inquiring man who read widely and voraciously tens of subjects – academic, every genre of literature, history, science and popular culture among them – and yet retained an uncanny ability to discuss, explain and comment upon them (or indeed anything else he turned to) in a manner that allowed lesser mortals like me to appreciate and understand them better, frequently for the very first time.

He was also a gregarious, generous, insightful and amusing broadcaster – attributes not always associated with writers – and above all, a natural entertainer and wit.

For a decade and more his weekly television reviews were the primary reason I routinely bought and read The Observer newspaper on Sundays.

For a decade and more his weekly television reviews were the primary reason I routinely bought and read The Observer newspaper on Sundays.

Elsewhere he wrote poetry and song lyrics.

If he wished, he could write about blancmange and make it both fascinating and hilarious.

He made TV documentaries, both serious and fluffy, and turned his hand seemingly effortlessly – though, of course, the art of doing so often lies in the hard work this requires – to chat shows, film review programmes and light entertainment reviews of weird games shows from around the world.

Whenever I think of Clive James I am often transported back to the classic autobiography he produced covering his early years – Unreliable Memoirs (first published in 1980) – which, to this day, I would still award the accolade of being the funniest book I have ever read.

Somehow it seemed to trigger by association vivid memories of one’s own childhood and youthful outlook and yet also – via its hindsight-driven and critical adult perspective – simultaneously offer thought-provoking insights and observations about those far-off times, his in Australia and mine in the UK.

Somehow it seemed to trigger by association vivid memories of one’s own childhood and youthful outlook and yet also – via its hindsight-driven and critical adult perspective – simultaneously offer thought-provoking insights and observations about those far-off times, his in Australia and mine in the UK.

To finish, if Rusters will allow me the indulgence, I am going to offer one of my favourite passages from Unreliable Memoirs.

It made me laugh out loud – and long – the first time I read it. I have returned to it many times over the past four decades and it never fails to make me smile.

Let me set the scene:

Our hero is describing his family life when he was aged somewhere between six and ten and here he introduces and describes his grandfather:

‘I remember him as a tall, barely articulate source of smells. The principal smells were of mouldy cloth, mothballs, seaweed, powerful tobacco and the tars that that collect in the stem of a very old pipe. When he was smoking he was invisible. When he wasn’t smoking he was merely hard to pick out in the gloom. You could track him down by listening for his constant, low-pitched, incoherent mumble. From his carpet slippers to his moustache was twice as high as I could reach. The moustache was saffron with nicotine. Everywhere else he was either grey or tortoiseshell mottle. His teeth were both.

I remember he bared them at one Christmas dinner. It was because he was choking on a coin in a mouthful of plum pudding. It was the usual Australian Christmas dinner, taking place in the middle of the day. Despite the temperature being 100 degrees F, in the shade, there had been the full panoply of ragingly hot food, topped off with a volcanic plum pudding smothered in scalding custard. My mother had naturally spiced the pudding with sixpences and threepenny bits, called zacs and trays respectively. Grandpa had collected one of these in the oesophagus. He gave a protracted, strangled gurgle which for a long time we took to be the beginning of some anecdote. Then Aunty Dot bounded out of her chair and hit him in the back. By some miracle she did not snap his calcified spine. Coated with black crumbs and custard, the zac streaked out his mouth like a dumdum and ricocheted off a tureen.

I remember he bared them at one Christmas dinner. It was because he was choking on a coin in a mouthful of plum pudding. It was the usual Australian Christmas dinner, taking place in the middle of the day. Despite the temperature being 100 degrees F, in the shade, there had been the full panoply of ragingly hot food, topped off with a volcanic plum pudding smothered in scalding custard. My mother had naturally spiced the pudding with sixpences and threepenny bits, called zacs and trays respectively. Grandpa had collected one of these in the oesophagus. He gave a protracted, strangled gurgle which for a long time we took to be the beginning of some anecdote. Then Aunty Dot bounded out of her chair and hit him in the back. By some miracle she did not snap his calcified spine. Coated with black crumbs and custard, the zac streaked out his mouth like a dumdum and ricocheted off a tureen.

Grandpa used to take me on his knee and read me stories, of which I could understand scarcely a word, not because the stories were over my head but because his speech by that stage consisted entirely of impediments. “Once upon a mpf …”, he would intone, “there wah ngung mawg blf …’.My mother got angry with me if I was not suitably grateful to Grandpa for telling me stories. I was supposed to dance up and down at the very prospect. To dodge this obligation I would build cubbyholes. Collecting chairs, cushions, bread boards and blankets from all over the house, I would assemble them into a pillbox and crawl in, plugging the hole behind me. Safe inside, I could fart discreetly while staring through various eye-slits to keep track of what was going on. From the outside I was just a pair of marsupial eyeballs in a heap of household junk, topped off with a rising pall of sulphuretted hydrogen. It was widely conjectured that I was hiding from ghosts. I was too, but not as hard as I was hiding from Grandpa. When he shuffled off to bed, I would unplug my igloo and emerge. Since my own bedtime was not long after dark, I suppose he must have been going to bed in the late afternoon. Finally he went to bed altogether.’