The ‘art’ of keeping a diary

Way back in 1989 – I just looked this date up on the internet – I bought an excellent anthology of diary entries entitled Each Returning Day: The Pleasure of Diaries, edited by a gent named Ronald Blythe.

I no longer have my copy, but I remember it fondly partly because at the time I was in the habit of writing a diary myself for a number of reasons, some of them no doubt obscure and self-revelatory (perhaps in a subconscious and/or unintended manner), and some of which I was probably incapable of explaining, or was it ‘articulating’?

In his introduction or preface Mr Blythe reviewed the various reasons that diary-writers do what they do. As you’d expect, some of them were glaringly obvious or understandable and others were rather deeper, darker, or strange (well, unless the reader was sympathetic to the viewpoint of the person writing the diary concerned).

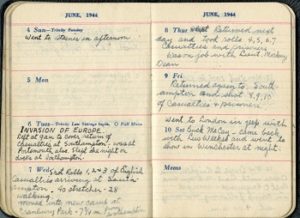

Some wrote diaries simply as a form of ‘creative habit’ – simply as a means to doing no more than produce a short expanded version of their engagement diary, in case perhaps one day in the future they might ever need to go back and remind themselves what they were doing on a particular day in the past. Not necessarily that they ever expected to wish to do this, but at least (if they should ever) at least something would be there to examine.

Others were motivated by self-justification. For example, at times of private life and/or career crisis, (as it were) setting in stone their version of events as they unfolded – in case (legal actions, vindication?) at some point in the future ‘proof of evidence’ might be required to defend themselves, and of course ‘contemporaneous notes’ are often recognised by courts and other authorities as being helpful in terms of establishing what (and indeed the ‘weight’ of what) was happening at any particular point – that is, as for example compared to ‘recollections of what happened’ recalled perhaps months or even decades after the actualitè.

Still others were writing diaries or journals ‘for the future’ – perhaps one day to be read by their family descendants, or indeed by the public at large (in the latter case perhaps having bought a published copy of said diaries). Many of these would (again) be self-justificatory efforts and – if you should wish to look at it from this viewpoint – never mind the obvious hoped-for lucrative advance (and subsequent millions to be gained from hitting the best-seller lists), somehow designed to ‘get the writer’s retaliation in first’ and/or put out there a version of events as the author’s ‘contribution’ to the world’s understanding of the events – great or small – in which he or she had been involved.

Still others were writing diaries or journals ‘for the future’ – perhaps one day to be read by their family descendants, or indeed by the public at large (in the latter case perhaps having bought a published copy of said diaries). Many of these would (again) be self-justificatory efforts and – if you should wish to look at it from this viewpoint – never mind the obvious hoped-for lucrative advance (and subsequent millions to be gained from hitting the best-seller lists), somehow designed to ‘get the writer’s retaliation in first’ and/or put out there a version of events as the author’s ‘contribution’ to the world’s understanding of the events – great or small – in which he or she had been involved.

The other main advantage of producing a published diary – or indeed autobiography – is that inevitably it allows the author to ‘control’ at least some of the narrative. Some of the disastrous property investments, love affairs, deceits and ‘negative’ aspects of their lives can be left out, brushed aside or explained away (as per one’s choice) whilst the supposed successes, triumphs and achievements can be ‘bigged up’ for the paying public to enjoy …. and hopefully thereby also think the better of them.

What I was most interested in, however, amongst Mr Blythe’s run through of diary-writer motivations, were those slightly more ‘off the wall’.

One of them was the compulsion to record. Its adherents amounted to a minority subset – albeit a significant one. Some people just felt an urge to record what they did. Samuel Pepys was one such. The proof was in the pudding. The more he did, the more he recorded. This ‘feels’ counter-intuitive, because you’d think that … the more you crammed into any particular day … with one human thing and another (food, comfort breaks, rest, even slumber) … you’d think that logic would demand you’d have less time to set down what you’d been up to on paper (or whatever) and that therefore you’d write less, or alternatively just leave some of it out.

But no. As stated, those possessed of a diary-writing ‘compulsion to record’ seem to have the need to set down whatever they’ve been doing (good or bad) and that’s simply that.

In examining my own case – which I did not infrequently, especially towards the end of my diary-writing stint when I was asking myself why the hell I was doing it and actually not coming up with any significantly logical or convincing answers, well perhaps beyond a worrying suspicion that I’d hate myself and/or feel a huge sense of regret if I ever stopped – I came to the conclusion that – if, for example, I should ever wish (or have the need) to go back into my life and find out what I had been doing – or perhaps even thinking – on a particular day, I would have my diary in which to find that out.

In examining my own case – which I did not infrequently, especially towards the end of my diary-writing stint when I was asking myself why the hell I was doing it and actually not coming up with any significantly logical or convincing answers, well perhaps beyond a worrying suspicion that I’d hate myself and/or feel a huge sense of regret if I ever stopped – I came to the conclusion that – if, for example, I should ever wish (or have the need) to go back into my life and find out what I had been doing – or perhaps even thinking – on a particular day, I would have my diary in which to find that out.

That was the theory I developed, anyway. But it was slightly more complicated, or maybe troubling, than that. Because, on a day to day basis, I deliberately never ever went back to look up what I’d written in a previous entry … one day, one month, one year, or even one decade previously … because I didn’t want to know. It was as if – having set down all that I’d done the previous day – I could wipe my mental hard drive memory clean with a clear conscience – forget the bloody day, if you like – because [yes, you’re ahead of me!], of course, if necessary I could always later go back to said diary entry and look it up.

I also worried that, if I did ever go back and read what I’d written previously, it then might affect what I then wrote in the future.

For example, if A behaved like a complete shit towards me or those I loved, a reference to this might appear in my diary. If ever I was subsequently to go back and read that entry I might think “Actually, A wasn’t quite as bad as all that, maybe when I next write about him I should say something to that effect in order to clarify the position, or be fair to him, in the interests of giving a more considered view of his personality …”.

And that would be wrong. I should react to whatever A did on any particular day ‘in the moment’. Maybe two hundred years’ time, some researcher might find my diary in the back of an old bookshelf and discover that – of 30 mentions I made of A in total, in 23 of them he did shitty things … so (in the round, overall) the impression I’d given posterity of him being a shit would be probably fair and accurate!

I just thought I’d share these thoughts today with my Rust readers.

It’s got nothing to do with the fact that I haven’t posted anything to the website recently. That’s because I’ve either being doing not a lot, or at least nothing of interest enough that it is worthy of being shared with anyone!