The memorial service for Ken Howard

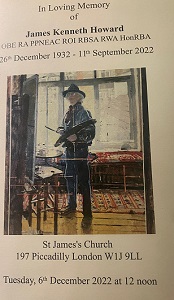

Last Tuesday I attended the memorial service for Ken Howard which took place at St James Church Piccadilly and afterwards at the Royal Academy.

The church memorial takes an hour into which time you have to fit in prayers and the life of the person, in the case of Ken a full and long one.

The church memorial takes an hour into which time you have to fit in prayers and the life of the person, in the case of Ken a full and long one.

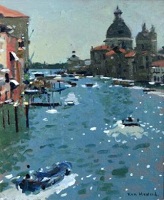

An ensemble played music from Vivaldi which was appropriate as he was Venice’s most famous composer and Ken had a studio in that city.

A brochure was distributed with many photos of Ken – including one receiving his CBE received from Princess Anne – and others of his homes: the studios in the Boltons, once belonging to society painter William Orpen; Mousehole near Penzance; and Venice.

Ken came from a poor working family in Neasden, North London, but grafted his way to the top.

He was a distinguished trainee with the Royal Marines, where his early painting talent was recognised with a commission – not to become an officer – but to paint a portrait of one that had been requested by the Sergeant’s Mess.

The military connection continued when the Imperial War museum commissioned him as its official artist in Northern Ireland at the time of the Troubles.

Those who bracket Ken as only a pretty illustrator of light would do well to revisit his triptych of Belfast, which depicts the anger in the Province.

Those who bracket Ken as only a pretty illustrator of light would do well to revisit his triptych of Belfast, which depicts the anger in the Province.

He worked as a teacher in art schools, where he befriended many artists who were to make an impact: David Hockney, for example.

As one eulogist of Ken in the service pointed out, for somebody whose credo was not to belong, he certainly did to many art institutions notably the Royal Academy , where he was admitted as a full Academician and later Professor of Perspective.

Ken painted in a familiar style against the light known as ‘contre jour’. In the battle that raged in British art between abstract and figurative art Ken wore the standard of the latter.

Ken painted in a familiar style against the light known as ‘contre jour’. In the battle that raged in British art between abstract and figurative art Ken wore the standard of the latter.

His paintings always sold well at exhibitions of the New Grafton Gallery and Richard Green, but critical acclaim was more elusive as I never saw his work given exhibition status by a museum.

He was not just a great artist, but a great man.

He was not just a great artist, but a great man.

There was never a dull moment in his company, often with red wine in hand; he told amusing stories and was as happy to talk of Georges Braque as a fauvist as about his beloved Chelsea FC.

He was a brilliant salesman, earning him the nickname “Ken High Street”.

Whilst a fitting and noble tribute, it was also a sad one – a time for reflection and remembrance.

One of the two great loves of Ken was his second wife Christa Gaa (the second was his third wife Dora Bertolucci).

One of the two great loves of Ken was his second wife Christa Gaa (the second was his third wife Dora Bertolucci).

As a poor and unknown artist Gaa’s family in Germany was at first against their marriage. Ken noticed similarities with John Constable who married Mary Bickford, whose father was advisor to the Prince Regent, and in his time Constable was deemed unworthy.

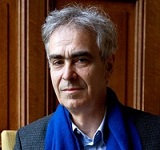

The art historian Martin Gayford had written an biography of Constable so I hosted – at Ken ‘s request – a dinner at the Chelsea Arts Club for the three of us.

The art historian Martin Gayford had written an biography of Constable so I hosted – at Ken ‘s request – a dinner at the Chelsea Arts Club for the three of us.

It was a dinner which – quite unlike me – I was happy to sit back and listen.

Martin’s scholarship is peerless but Ken was a fund of art knowledge too, as he always was.

He was dressed in a cape and rakish black Borsalino hat and had perhaps come a long way from the star trainee of the Royal Marines at Lympston.

He was dressed in a cape and rakish black Borsalino hat and had perhaps come a long way from the star trainee of the Royal Marines at Lympston.

It was quite a journey and the memorial service reflected it beautifully.